The concept of probability is ubiquitous in our modern world, but how does it work, and how do we construct these tools from the ground up?

The Probability Space

The underlying tool we will use for probability is our probability space, this consists of 3 main items

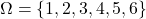

, the sample space, which is the collection of outcomes.

, the sample space, which is the collection of outcomes. , the event space, which is the collection of possible events, which are collections of elements of the sample space.

, the event space, which is the collection of possible events, which are collections of elements of the sample space.![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \mathbb{P}: \mathcal{F} \to [0,1]](https://blog.samuelgill.net/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-61ba77d7a7503ae46199311c9933f370_l3.png) , the probability map, which gives the probability of a given event.

, the probability map, which gives the probability of a given event.

Example

Let’s take the example of a ![]() sided dice roll…

sided dice roll…

would be the possible outcomes, so

would be the possible outcomes, so

would be all possible combinations of elements of

would be all possible combinations of elements of  . This is because not only are there events such as the die lands on

. This is because not only are there events such as the die lands on  (Which would be

(Which would be  ), but there are also the events such as the die lands on an even number (Which would be

), but there are also the events such as the die lands on an even number (Which would be  ).

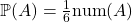

).- Provided the die is fair, then

would simply be

would simply be  , where

, where  is the number of elements in

is the number of elements in  .

.

Axioms of Probability

These then obey certain axioms of probability. First, ![]() must be a

must be a ![]() -algebra on

-algebra on ![]() . This is a type of structure that follows these 3 main properties.

. This is a type of structure that follows these 3 main properties.

Or in other words

- The event of nothing is an event

- If some event can happen, then it not happening is also an event that can happen.

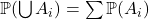

- If

are a list of events that can happen, then the event that any of

are a list of events that can happen, then the event that any of  occur is an event that can happen.

occur is an event that can happen.

And ![]() must follow the following axioms.

must follow the following axioms.

- Given

disjoint, then

disjoint, then

Which means that,

- The probability that any outcome will happen is 1, or in other words, at least one outcome must happen.

- The probability of any event must be

.

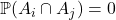

. - Given any

such that they don’t intersect, meaning

such that they don’t intersect, meaning  (which although not technically true, one can think of this as

(which although not technically true, one can think of this as  ), then the probability of any of the events happening is the same as the sum of the probabilities of each event.

), then the probability of any of the events happening is the same as the sum of the probabilities of each event.

Bayes Theorem

Now that we have defined our probability function, we can use it to dicover some facts about the probability of events. Note for all the future discussions we need to assume, unless stated otherwise, all probabilities will be ![]() , this simplifies some of the upcoming work.

, this simplifies some of the upcoming work.

One important tool for this is going to be the symbol ![]() , which in words means “given”. Thus

, which in words means “given”. Thus ![]() means the probability that the event

means the probability that the event ![]() occurs, given the event

occurs, given the event ![]() occured. We also need to define something called a partition, this is a colleciton of events

occured. We also need to define something called a partition, this is a colleciton of events ![]() for

for ![]() such that all

such that all ![]() are disjoint, and together

are disjoint, and together ![]() . Or in words, this is a collection of events such that exactly one of them will occur. For example if we are rolling a die, the partition could be

. Or in words, this is a collection of events such that exactly one of them will occur. For example if we are rolling a die, the partition could be ![]() being the number is odd and

being the number is odd and ![]() being the number is even.

being the number is even.

The first fact that will be of use for us is that

This actually does not need a proof, as this is the definition of what ![]() is (In our current logic, the actual definition is far more complex and beyond the scope of this post).

is (In our current logic, the actual definition is far more complex and beyond the scope of this post).

Law of total probability

The first consequence of our defintions above is the law of total probability (LTP), which states that given a partition ![]() , then

, then

The proof of this fairly simple, but will be ommitted here (See if you can do it yourself!).

What does this tell us? Essentially, this tells us that if we have an event, the probability that it occurs can be divided into some fractions of the probability of the partitions occuring, based on the chance that our event occurs given a partition occurs.

Bayes Theorem.

You may have noticed that we can rearrange the formula for ![]() and realised we can rearrange it to get a formula for

and realised we can rearrange it to get a formula for ![]() , which is symmetric in

, which is symmetric in ![]() and

and ![]() , thus

, thus

Hence,

This is Bayes theorem (Some people use the law of total probability on ![]() in their statement). Essentially it tells us that we can reverse conditional probabilities.

in their statement). Essentially it tells us that we can reverse conditional probabilities.

Random Variables

The next key tool in the study of probability is that of the random variables. We can think of these as objects with a random value, such as the value on a die, the number of people in a room, or the height of a person.

There are ![]() main types of such variables, these are continuous and discrete. Technically a random variable can be neither, but this only occurs in specific circumstances which wont be disscussed here.

main types of such variables, these are continuous and discrete. Technically a random variable can be neither, but this only occurs in specific circumstances which wont be disscussed here.

The basic construction

A random variable is a map from ![]() to some output space,

to some output space, ![]() . Very commonly

. Very commonly ![]() will be

will be ![]() , although this does not need to be the case, we shall assume

, although this does not need to be the case, we shall assume ![]() from now on. We also require that a random variable satifies that the set

from now on. We also require that a random variable satifies that the set ![]() is an event. This then lets us give a value to each possible event, for example if

is an event. This then lets us give a value to each possible event, for example if ![]() was the year a person was born, then if

was the year a person was born, then if ![]() was the event that we chose Kurt Gödel, then

was the event that we chose Kurt Gödel, then ![]() . We could then say what is the probability that the age of a person is

. We could then say what is the probability that the age of a person is ![]() , or more formally, what is the value of

, or more formally, what is the value of ![]() , this is often shortened to

, this is often shortened to ![]() . This in words is then the probability that the sampled event is an event that gives the year

. This in words is then the probability that the sampled event is an event that gives the year ![]() .

.

If X has finite or countably many outputs, then its discrete, and hence by the axioms above, ![]() is then an event. We can then define

is then an event. We can then define ![]() , we call

, we call ![]() the probability mass function.

the probability mass function.

The defintion of a contionous random variable is more complex, as we can’t say that ![]() is an event, so instead we say

is an event, so instead we say ![]() is continuous if there exists a function

is continuous if there exists a function ![]() such that

such that ![]() for all

for all ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and

Here we call ![]() the cummulative density function, and

the cummulative density function, and ![]() the probability density function.

the probability density function.

Why?

With this, we can define some useful properties, first we could want to consider the mean (or average) of a random variable, to do this we will define the expectation, this is expected value a random variable will give us, and is denoted ![]() . For discrete random variables, this is calculated by

. For discrete random variables, this is calculated by

![]()

Or in words, the expectation is the weighted average of all the outcomes, weighted by the probability of getting that outcome. Then for moving into the continous case, we replace sums with integrals to get

Which in meaning is very similar to above, just using integrals.

Another property we could define is variance, here we will use the expectation to say the variance is the expected square (as so to make it positive) distance from the mean, and hence is calculated

Or the much easier to compute version

One could then choose to square root this and get the standard deviation, denoted ![]() .

.

No Responses