One of the most important areas of mathematics is that of calculus, but how we actually define the tools we use in calculus is one which is very biased, many courses teach the definition of a derivative, but few rarely cover the definition of the integral, this is what we will cover here.

A recap of the Derivative

Before we cover the integral, we should first practice a bit of hypocrisy and cover the defintion of the derivative, this will serve as both a useful introduction, but will also help us later when we try and link the two.

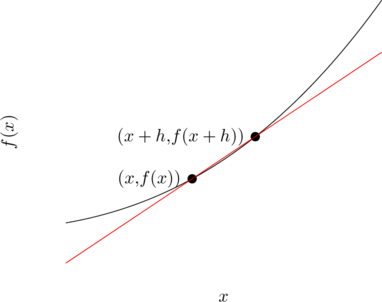

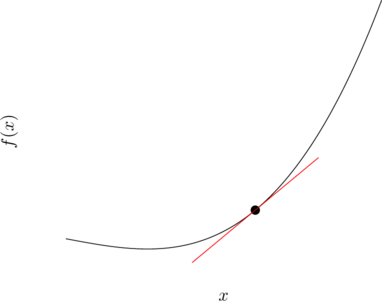

As you may know, the derivative is the gradient of the tangent line at a point on a function, so lets see if we can find a definition from the derivative from this.

One way we could view the derivative is by looking at the line between two points on the curve, one at ![]() and one slightly further ahead, say at

and one slightly further ahead, say at ![]() , now lets look at the line between them

, now lets look at the line between them

Now we can move ![]() closer and closer to 0, we can see the two points get closer and closer together, and eventually, this will become the tangent, so how do we calculate this gradient? Well you may know that the gradient of a line between two points

closer and closer to 0, we can see the two points get closer and closer together, and eventually, this will become the tangent, so how do we calculate this gradient? Well you may know that the gradient of a line between two points ![]() and

and ![]() is

is

![]()

So subsituting in our points, we get,

![]()

So now, we can take ![]() to get smaller and smaller, this gives us a limit, so we can say that the derviative of a function

to get smaller and smaller, this gives us a limit, so we can say that the derviative of a function ![]() assuming such a thing exists, is defined as follows

assuming such a thing exists, is defined as follows

![]()

As you might have guessed from the previous sentence, the above limit does not always exist, this can cause a problem as then ![]() would be undefined, there are various ways to check this, but for now we are going to assume that all these derivatives exist.

would be undefined, there are various ways to check this, but for now we are going to assume that all these derivatives exist.

Now lets do that again for an integral!

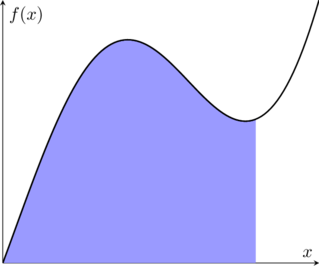

One way to view the integral is that of the area under a curve, so lets see if we can figure a way out to do this same stratgey with the integral

Now there are many ways to go now, and many ways to define the integral, the ![]() main ones are the

main ones are the

- Darboux Integral

- Riemann Integral

- Lebesgue Integral

We will cover the first Integral here. The other two are still very interesting, and actually the first two are interchangable. But the later two are also more complex, although maybe I’ll do another post about it.

Useful tools for all Integrals

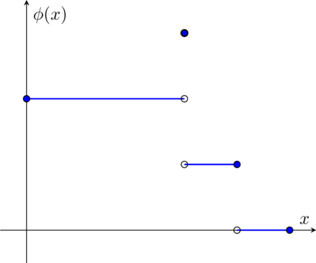

One of the most useful tools we will use here is that of a step function. A step function is one that takes constant values over certain areas of an interval, for example, the following function ![]() is a step function.

is a step function.

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \phi(x) = \begin{cases} 2 & x\in [0,3) \\ 3 & x = 3\\ 1 & x\in (3,4] \\ 0 & x \in (4,5] \end{cases}\]](https://blog.samuelgill.net/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-e3f767a606423ab8249800aebf821dcf_l3.png)

Here, the set of values, ![]() is called the partition of

is called the partition of ![]()

Darboux Integral

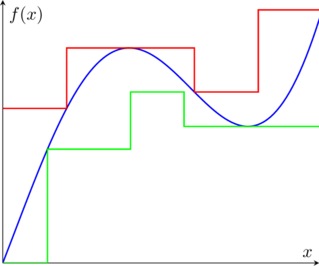

Now that we have those tools defined, we can work towards the Darboux Integral, to do this we need to define a minorant and a majorant, these are step functions which are either always greater or always lesser than the target function, for example we can draw some on the previous image as such

Now we can easily compute the area under a step function, over a partition of the form ![]() with the step function

with the step function ![]() taking the value

taking the value ![]() on the interval

on the interval ![]() (Note we dont care about what value the function takes on points, as they dont contribute the the area at all). The “psudeo” Integral of this step function,

(Note we dont care about what value the function takes on points, as they dont contribute the the area at all). The “psudeo” Integral of this step function, ![]()

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[I(\phi) = \sum_{k=1}^{n} \lambda_k (x_k - x_{k-1})\]](https://blog.samuelgill.net/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-ca395cf934e2adeb82ca9692212d4256_l3.png)

Which you can interpret as the area of the rectangles under the step function.

Now we can actually define the Darboux Integral, using the tools of the supremium and infemum, letting ![]() be the set of majorants, and

be the set of majorants, and ![]() be the set of minorants, thenthe Darboux Integral equals

be the set of minorants, thenthe Darboux Integral equals

![]()

Asuming the infiumum and supremum are equal.

No Responses