There is a common joke among mathematicians that a topologist can not tell the difference between a cup of coffee, and a doughnut, but why is this, and how does one topologically define these structures?

What is a topology?

A topology is a way of looking at subsets of a larger set, using a topology we can qualify certain sets as “open”, or “closed”. In the context of a topology, the idea of an open set is fairly meaningless, a set is open as we just state that it is open. However later on we shall be working in ![]() where we can view open sets through the lens of a metric space, where there is a nice intuition for what we could call open.

where we can view open sets through the lens of a metric space, where there is a nice intuition for what we could call open.

One example of this is in ![]() , here open sets

, here open sets ![]() are such that

are such that

![]()

![]()

As a concrete example, in ![]() ,

, ![]() is open as we can always find a region around x no matter how close to the edge we get, on the other hand

is open as we can always find a region around x no matter how close to the edge we get, on the other hand ![]() is not open, as at the edges, no matter how small we make our distance, we will always have some points not in the set.

is not open, as at the edges, no matter how small we make our distance, we will always have some points not in the set.

As a side note, one may think of closed as not open, but this is not true, we say a set is closed if its compliment (All points which are not in the set) is open. However this can lead to the cases where a set is neither open or closed (We could think about ![]() where there is no ball around

where there is no ball around ![]() in the set, and no ball around

in the set, and no ball around ![]() in the compliment), or where the set is both open and closed (We could look at the full space

in the compliment), or where the set is both open and closed (We could look at the full space ![]() , as it’s open trivially, and its compliment is the empty set, so has a ball around all it’s elements – for which there are none).

, as it’s open trivially, and its compliment is the empty set, so has a ball around all it’s elements – for which there are none).

What actually is a topology?

Given a set ![]() , we can define a topology

, we can define a topology ![]() as a collection of subsets of

as a collection of subsets of ![]() which have the following properties.

which have the following properties.

Given ![]() and

and ![]() with

with ![]() arbitrary, and

arbitrary, and ![]() finite, then,

finite, then,

(1)

But what does this mean?

![]() tells us that our topology must contain

tells us that our topology must contain ![]() , the empty set and

, the empty set and ![]() , the full space.

, the full space.

![]() tells us that an arbitrary union of sets in our topology must remain in our topology

tells us that an arbitrary union of sets in our topology must remain in our topology

![]() tells us that a finite intersection of sets in our topology must remain in our topology.

tells us that a finite intersection of sets in our topology must remain in our topology.

We can then call the elements of our topology the open sets.

An exercise to the reader would be to show that the definition we gave of open sets in the first section obey all these rules. One could also show that we can’t extend this to an arbitrary intersection, one can find an infinite number of sets such that their intersection is not in the topology.

Continuous maps

We will also use the concept of a continuous map. A map is a function from one space to another, one could for instance have ![]() given by

given by ![]() , here map

, here map ![]() maps from

maps from ![]() to

to ![]() .

.

Now there are a variety of ways to define a continuous map, in a topology the only way we can abstractly define it is to say the preimage of open sets are open. So if ![]() , then

, then ![]() is continuous if

is continuous if ![]() open in Y, then

open in Y, then ![]() is then open in X. This is a very useful definition for proofs, however it is not very useful to visualise, so again we can find an equivalent definition in a metric space.

is then open in X. This is a very useful definition for proofs, however it is not very useful to visualise, so again we can find an equivalent definition in a metric space.

Here we can say that ![]() is continuous at

is continuous at ![]() if

if ![]() ,

, ![]() such that

such that ![]() with

with ![]() implies that

implies that ![]() . We can think of this as for each ball around the point

. We can think of this as for each ball around the point ![]() , we can find some region around

, we can find some region around ![]() such that all points in this second region land in the first ball when you apply

such that all points in this second region land in the first ball when you apply ![]() .

.

Quotient Spaces

Now we can start to construct our doughnut. To do this we will use the concept of a quotient space.

Lets start with our topological space ![]() . We now want to get an equivalence relation on the space, I have defined these before, but for a quick recap, we can think of these as a quality between two elements. We can then say

. We now want to get an equivalence relation on the space, I have defined these before, but for a quick recap, we can think of these as a quality between two elements. We can then say ![]() if it’s true (said

if it’s true (said ![]() relates to

relates to ![]() ), a relation is then equivalent if it is reflexive (

), a relation is then equivalent if it is reflexive (![]() for all

for all ![]() ), symmetric (if

), symmetric (if ![]() , then

, then ![]() ) and transitive (if

) and transitive (if ![]() and

and ![]() then

then ![]() ). We can then think of the equivalence class of

). We can then think of the equivalence class of ![]() , written

, written ![]() or

or ![]() , as the set of elements which then relate to

, as the set of elements which then relate to ![]() .

.

Lets now have an equivalence relation ![]() on

on ![]() , now let

, now let ![]() denote the set of equivalence classes, we now want to construct a topology on

denote the set of equivalence classes, we now want to construct a topology on ![]() , we do this through the concept of a collapsing map, this is the map

, we do this through the concept of a collapsing map, this is the map ![]() from

from ![]() to

to ![]() given by

given by ![]() . We then define a topology

. We then define a topology ![]() where

where

![]()

So what does this mean?

We can think of this as any ![]() as a collection of equivalence classes, then

as a collection of equivalence classes, then ![]() is then the elements in

is then the elements in ![]() which are in an equivalence class in

which are in an equivalence class in ![]() . Hence

. Hence ![]() is then open if the collection of elements which are in the equivalence classes of U is open.

is then open if the collection of elements which are in the equivalence classes of U is open.

Constructing our Doughnut

In order to get an idea of how the above construction works, lets start making our doughnut.

Ingredients

To start making our doughnut, we first need an underlying space, this will be our ![]() , and in this case we will consider

, and in this case we will consider ![]() , which all pairs of numbers

, which all pairs of numbers ![]() such that

such that ![]() .

.

We then need a topology on our space ![]() , we will do this by saying

, we will do this by saying

![]()

We can think of this as ![]() is open in

is open in ![]() if we can find a region around each point in

if we can find a region around each point in ![]() of points in

of points in ![]() , note this does not include points that lie outside of

, note this does not include points that lie outside of ![]() , as we are only considering those points.

, as we are only considering those points.

Recipe

Now we also need to construct an equivalence relation on this set, in this case we will use that ![]() if either

if either ![]() and

and ![]() or

or ![]() and

and ![]() or the same with swapping the coordinates, so

or the same with swapping the coordinates, so ![]() and

and ![]() or

or ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

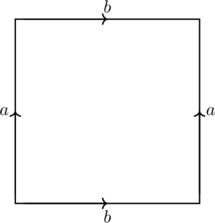

We can then picture this by

Now, we can visualise the quotient topology as sticking together these lines in such as way as we preserve the direction of the arrows, thus giving…

…our doughnut, we can now see that for any point on the set, we can use our old definition of open, and this further allows us to do some much more in-depth mathematics on this surface, such as differentiation, through the use of a structure called a manifold, which this is an example of. I may cover this further in the future.

No Responses